11.6.13 Catherine Czacki

The quotes do not fit together seamlessly – they are akin to scraps of fabric that have not been sewn, floating near each other in time and space. Unlike their material friends, they reveal distinct opinions on matter and movement. Despite distance of time and or discipline, the quotes might in proximity perform a revelatory function regarding the problems within subject / object dialectics. The transcendental-self problem, the Other problem, the problem between subject and object in subject / object dialectics.

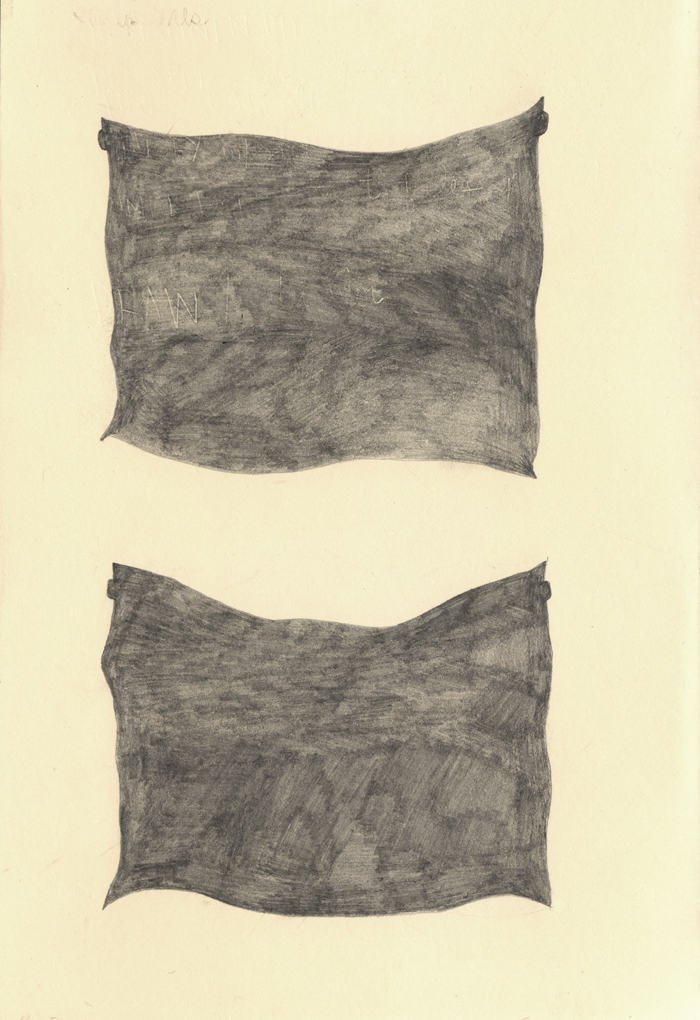

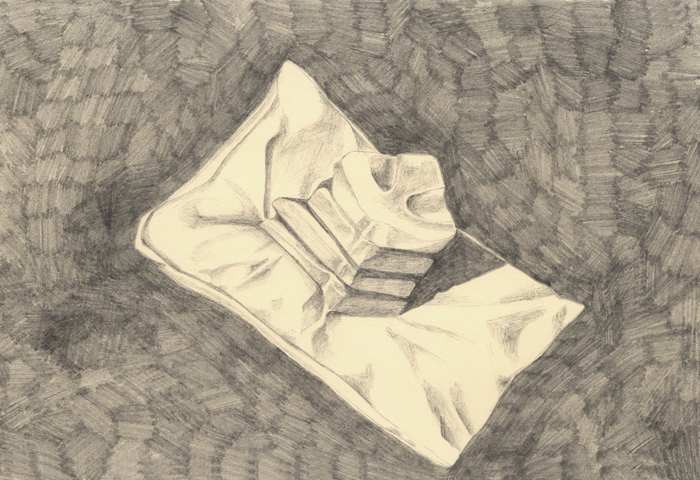

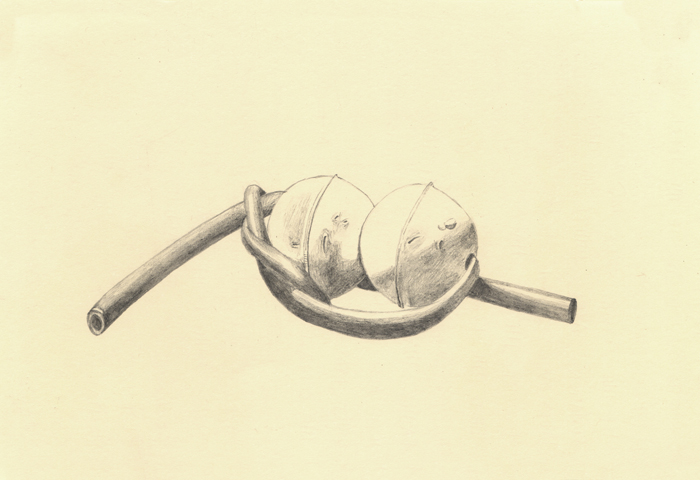

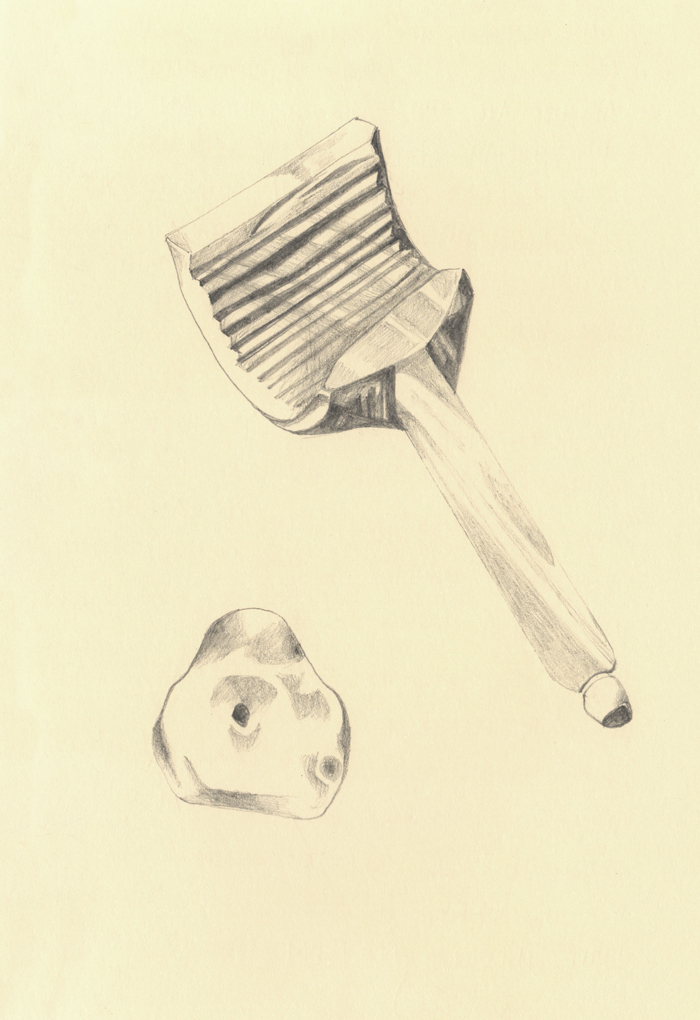

Images and words play together well. We can think they are autonomous, but they inform or deform each other endlessly. Whether explanation or obfuscation is the aim, words and things pair. Words are signs according to semiotics, and their original intention was to convey the world of things. Marks are made to convey information when the actual material is not present.

All of these quotes were found in the search for discussions regarding subject / object dialectics, and on the nature of things and human agency, in general. To classify and then re-classify the world of matter in the human epistemologically-centered world is difficult when trying to negotiate with history, while also trying to avoid speculative realism or techno-futuristic determinism, all with the knowledge that there are still issues with human agency in the world of Others and Things. I suspect the problem of human agency is intertwined with the problem of Things, or the problem of how we use and misuse the material world, maintaining a control of Others tied by their labor, and the ownership of Things and humans by some few. How labor is prized depends on manufacture and the movement of the ultimate of signs.

Everything moves quickly like the commodity, even if some of the more interesting themes and outcomes can arise from accumulation, seeing the oeuvre of an artist, thinker, or other cultural worker. The grand gesture does not reveal fissures in history, or allow for slow accumulation. It frequently repeats or elevates and therefore, the simplicity allowed through drawing and words is appealing. A few quotes and some light drawings might build to reveal something else. The making of utterances and images are some of the first creative acts. Before we knew of production and factories and the labor of others, we have our own hands and mouths to use, to describe the things and others in the world around us.

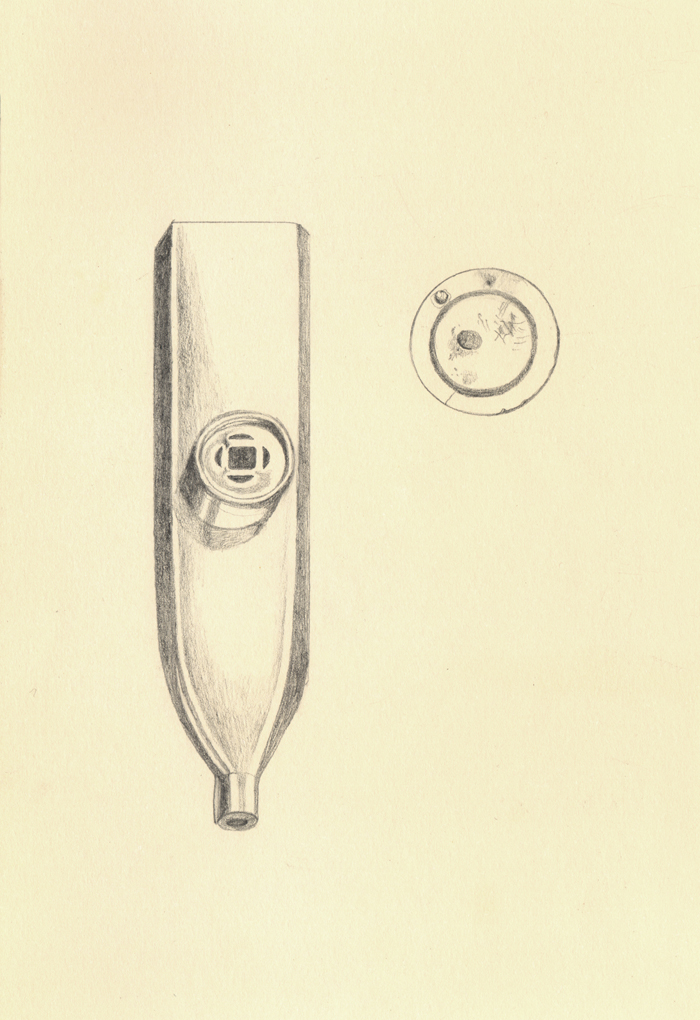

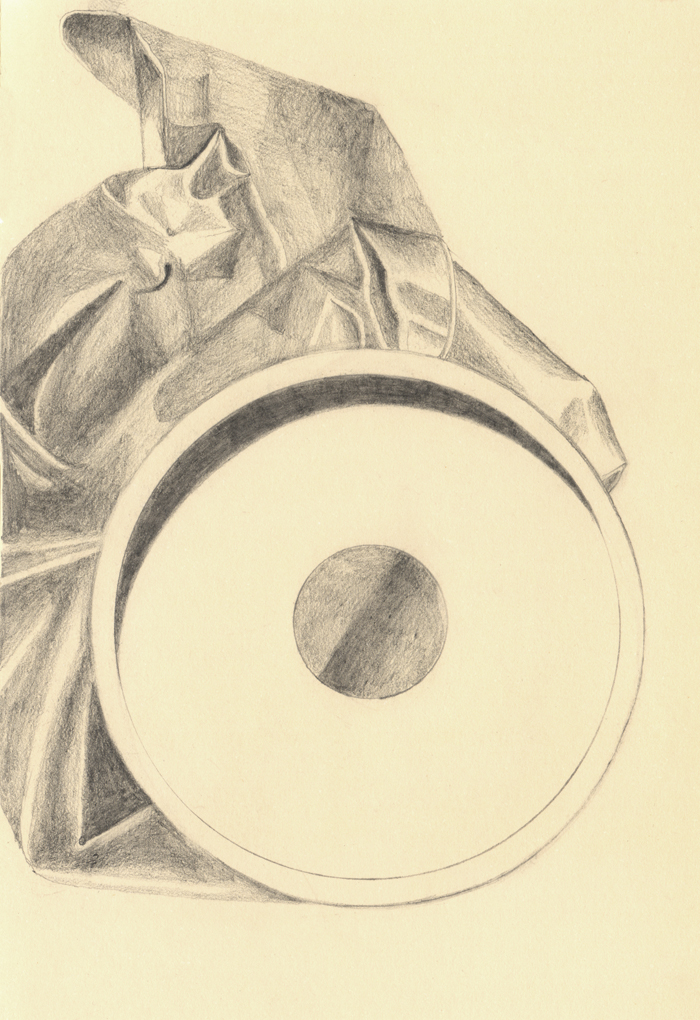

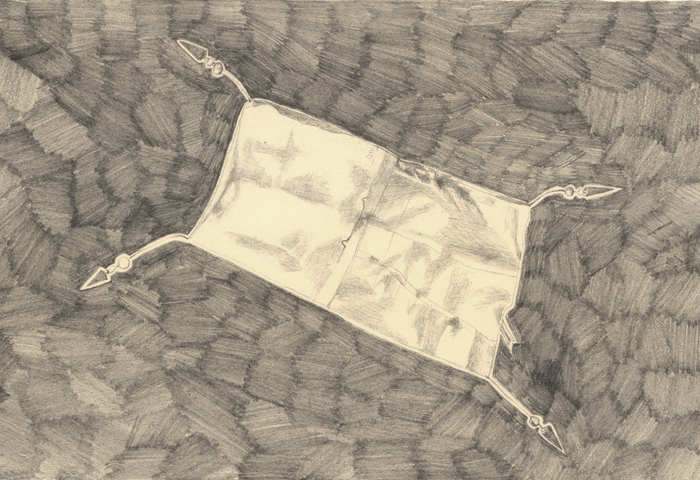

These pairings of drawings and quotes may not rupture order, or reveal truths. What they likely provide instead is a comparison between things and words, an old argument that continues to instigate human curiosity. What is the subject and what is the object – what is the Self and what is the Other.The distance between one’s eyes and the Thing is in fact a distance of matter, a distance often described by words that can reach the ears in a way that the depth within the matter might not. Drawing is a base for other modes of visual operations and form making. Scratching the surface, rendering another. Words and marks with a shared history – diverging friends.

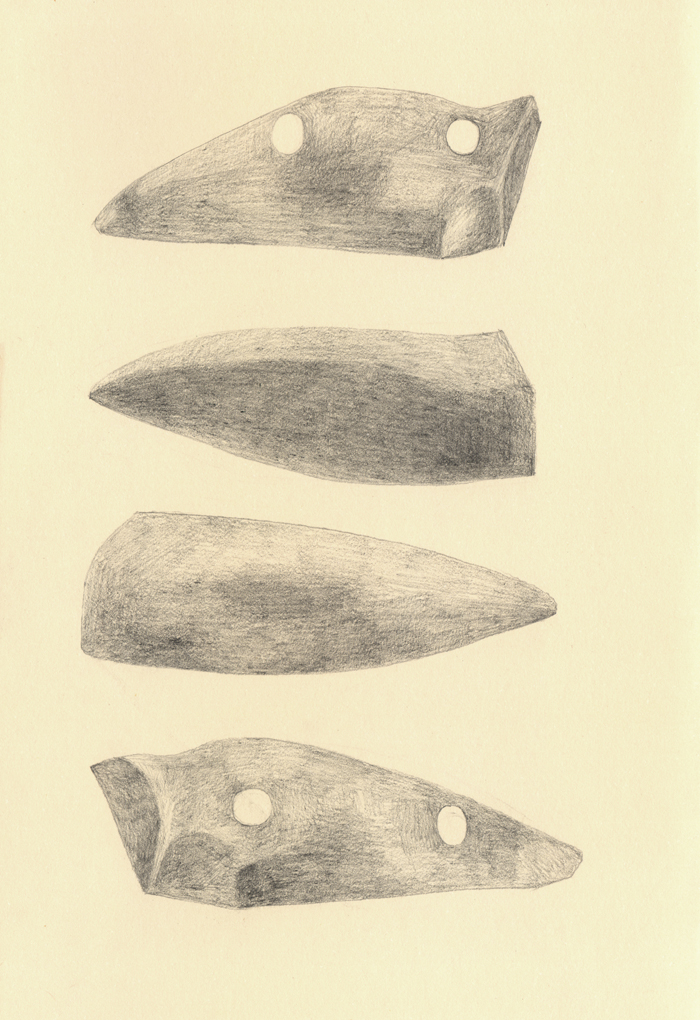

To look at an object or material and draw, is to familiarize oneself with every curvature and dent upon a surface. To think about how light recedes to darkness in the dips of matter, and how crests show the light growing ever closer before one’s vision, or to more accurately show that part of the object to be closer to the light of the sun or electrified source. The roughness or the smoothness of a surface depends on its material, silk versus burlap, perhaps.

In the process of seeing, the act occasionally completely misses the base, forgets the materials, forgets what each move requires in energy and resources.

The surrealists were into this game, and Walter Benjamin, too – that there is a troubled history underfoot with the Things, and with the Others. Things and Others, in fact, become relegated to lower positions in hierarchically-constructed situations. Things we bend to our will in the name of progress, while Others are those whose labor we utilize in order to continue this progress. As Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer point out, this progress had its grand failure after the Enlightenment, which did not provide the endgame Utopia it was supposed to, especially in regards to Things and Others. When myths leave, there is no ebb and flow, just a need to move forward.

Returning to the material at hand: the quotes and the drawings. Materials gather in the same fashion as quotes – they accumulate and sit, waiting for dispersal in other instances. The reason for this is never fully present at first. The reason will continually unfold, not to gain clarity but to record impulse.

This kind of process might fade when it is done, sliding back into the folds of history it, as a process, came from. Accumulation without endgame, dissolving like matter into liquid. These quotes are not meant to lend authority, only to aid complexity – material and subjectivity ad infinitum. Hopefully the drawings, like the quotes- despite being insubstantial on some level, without the real structure of a book- can be irrevocably solid in their pairings. Reading space into flatness, the simple archiving of thoughts and things.

Our structures of organizing knowledge about the world around us dictates how we deal with and in material, and how that material becomes entangled in our notions of progress and human agency. These thinkers, writers, and artists problematize what constitutes the base, the roots of reason, the nature of enlightenment, transcendental aims and negotiations between Self and Other, sentient or non. Through poiesis or analysis, they manage a variation of takes on the problems at hand, questioning our taxonomies and beliefs. Who is the Self and who is the Other, what is matter and what is mind. By no means comprehensive, this selection of quotes is only a reflection of what has been encountered thus far in this moment of continual accumulation.

With seemingly endless combinations of material that constitute our current push for the new and the durable, it is hard to train one’s vision and mind to the task of thinking on or of material – archiving all the materials into encyclopedic form, as Diderot once attempted with knowledge. Certain things seem to form a base of sorts- familiar, yet historically elusive. The distinction of raw and manufactured is elusive here. Maybe instead of thinking of material within the terms of permanence and newness, synthetic and raw, it would be useful to think in terms of flow, not just the lifespan of a material, but its relevance in and out of commodity culture. Water insists in being everything while containing no form, per se (unless you count ice), yet it is capable of breaking through stone.

An anthology of material:

Gold: having its day. Gold as commodity for the Europeans, a reason for trade with the Ivory Coast Baule people in early colonial times.

Paper: a fragile form, a technology developed for the inscribing of words on material – something that could last, while being more portable than stone; something that can harden like a rock, though it burns, burns away and leaves only the transformed version of itself, a carbon trace.

Stone is a material that, though hard, solid and forceful, can be cut by water.

Water carving and shaping stone is the elemental clash of material. The slow drive of the ephemeral liquid against the stolid longevity of the other. Working through time, water takes away the minerals and absorbs them into its own composition, dragging the components to other places to accumulate again in other shapes.

Wood: a cellular, living, breathing material. Wood is dead as soon as the tree stops breathing, but it still has the ability to breathe as a material. Wood in its porousness expands and contracts, changing shape even in its most solid outcome. Franz Boaz studied the cultures living in the Pacific Northwest of the United States – they created objects out of wood, deliberately made to be thrown into the ocean and last no longer than their maker. Wood was spoken to, asked for its forgiveness for being taken away from the living, forgiveness for the form it was about to take upon its death.

Fabric is a complicated material. It can be so many versions of a self; so many multiplicities to its composition are possible. Folds, and pleats, and folds upon folds. Weaving can be microscopic, produced by machines or woven with hands. Both the touched and the mechanized exist in this material, being natural depends on the molecular structure. This form of traditional arts survived for the colonized, noted in Oceanic cultures because missionaries saw this as women’s work – therefore, not a threat to those desiring power and control over the population. A complex technology frequently mistaken for raw material. That it was also intimately scaled made it easy to ignore.

Copper: archives the existence of the air it comes in contact with. It resists and inhabits time by always changing its color. Steel, plaster, concrete, ceramic – stone and metal – on and on. Silver, considered gold’s lesser friend, has also had its day, causing crises in China when it was mined to disappearance; desire for its return has led to unfavorable decisions and alliances.

Not to mention minerals, the hematites and the quartzes. Mud. Mud seems to be a good base. Mud contains the dead, the remains, the dirt- the archive of history-, within its layers.

Let us not forget the gasses and liquids either, though they are harder to pin or mark than the solids, always elusive in our ability to grasp them.

These are only a few examples, some simple ones – ones that are implicated in the march of progress. The synthetics multiply with such fervor, too large of a task to list. As these examples might indicate, raw and manufactured become insufficient monikers.

A question of material is a question of economics. For the modern model of progress to succeed, Things and Others are required to form a base for progress. How one deals with and in material, how much access one or many have to material, is indicative of what they are able to touch. Being removed from material, or rather able to buy the labor of others to produce materials that are then arranged, changes the relation to the material. The artist as master requires this model, as well; the fabrication of larger and larger statements indeed requires more and more labor, more and more material. Agents usually live at the top of the chain of being; those beneath are utilized to keep those agents transcending. Here, of course, we can thank Karl Marx for his work on the commodity, that ever changing material friend that we build entire systems of human cultural interaction around, and take from and hide underneath us those who are required to keep the circulation of wonderful material things going. It shines; it shines and blinds. What we keep seeming to end up with are the extremes. Either we are not allowed to desire the things at all – we must rid ourselves of the material and transcend; or, we must operate at a dizzying speed of production and newness and love of the more and more.

In the drawings that follow, between the quotes of others who occasionally think in, on, or of material, there is not a one-to-one relationship to the form that they were based upon. They may appear to be realistic depictions, or actual renderings, yet you would never confuse the real for the drawn. There are small deviations, areas where the hand takes over control of the representation of what the eye has seen. Moments where the eye lingers too long on the surface of charcoal dust rather than the object at hand. It is also unclear, through all this dust, what material composes the surface of the so-called original form that became a rendering. Materiality is altered in the trace, as tends to happen in repetition or copies (which also become things). Pencil lead – back to charred bones making marks. The power over matter presumed in the ability to represent. The shadow outline comes via Plato, objects being that which cast shadows, even when the shadow is a pencil line.

In Benjamin Buchloh’s essay, “Michael Asher and the Conclusion of Modern Sculpture”, he invokes a phrase by Marcel Proust on page 23: ‘All the gazes that objects have ever received seem to remain with them as veils’. I would amend that statement to say that all the words the objects have ever received sit atop them like an oily patina, not within but on top of the surface. Useful in some contexts, misleading in others. This realm of veils is possibly the most appropriate way in which to approach material, and to continue the challenge of thinking things and agents, surface and base.

* The quotes here are accumulations towards what will hopefully become a larger written work – including similar selections of words and objects, in production between now and roughly the year 2018. Special Thanks to Norman Bryson for making me look at objects closely and thoroughly, and to Mariana Razo Wardwell for reminding me to search for the base.

“Amazement is rediscovered, but it is an astonishment at individual things, not a Platonic amazement; an amazement saturated with nominalism and also emphatically opposed to the power of convention, which is a dingy lens in front of the eye and a layer of dust on the object … No ontology is to be extracted from the belly of the pot. What Bloch is after is this: if one only really knew what the pot in its thing-language is saying and concealing at the same time, then one would know what ought to be known and what the discipline of civilizing thought, climaxing in the authority of Kant, has forbidden consciousness to ask. This secret would be the opposite of something that has always been and always will be, the opposite of invariance; something that would finally be different.”[1] — Theodor Adorno

“The deep accumulation of dress fell about her in groined shadows; the train, rambling through a vista of primitive trees, was carpet-thick. She seemed to be expecting a bird.”[2] — Djuna Barnes

“There is moderation only in the object, reason only in the identity of the object with itself, lucidity only in the distinct knowledge of objects. The world of the subject is the night: that changeable, infinitely suspect night which in the sleep of reason, produces monsters. I submit that madness itself gives a rarified idea of the free “subject”, unsubordinated to the “real” order and occupied only with the present.”[3] — Georges Bataille

“It is a form of post-hypnotic suggestion that starts to work inside the body, as it were, at the moment the will abdicates its power once and for all in favor of the organs – the hand for instance. This is why you can look for something for days, until you finally forget it; then one day, when you are looking for something else, you suddenly find the first object. Your hand has, so to speak, taken the matter in hand and has joined forces with the object which had successfully resisted the dogged efforts of the will.”[4] — Walter Benjamin

“A cube, a sphere, a pyramid obeying the laws of the ocean. A cube, a sphere, a pyramid, a cylinder. A blue cube. A white sphere. A white pyramid. A white cylinder. We will not make any more moves. Silence. The species marches on with jabbering eyes. A green cube. A blue sphere. A white pyramid. A black cylinder. Like the dreams one hardly remembers; worlds where the shark, the knife, and the cook are synonyms. A black cube. A black pyramid. A sphere and a black cylinder. I prefer to close my eyes and walk into the night. The squid’s ink will describe the clouds and the distant earth. A yellow sphere. A yellow pyramid. A yellow cube that melts in the water, the air and the fire.”[5] — Marcel Broodthaers

“Although objects typically arrest a poet’s attention, and although the object was what was asked to join the dance in philosophy, things may still lurk in the shadows of the ballroom and continue to lurk there after the subject and object have done their thing, long after the party is over.”[6] — Bill Brown

“It is I singing with a voice still caught in the babbling of elements. It is pleasant to be a piece of wood a cork a drop of water in the torrential waters of the end and of the new beginning. It is pleasant to doze off in the shattered heart of things.”[7] — Aimé Césaire

“Of course, the very definition of a thing is problematic. In dictionaries a thing is defined as an entity having material existence; the real and concrete substance of an entity; an entity existing in time and space; an inanimate object. The word ‘object’ is used as a synonym (‘object’ is defined as a ‘material thing’. A ‘tangible and visible entity that can cast a shadow’).”[8] — Ewa Domanska

“Objects are the immediate future, in the sense of reaching out for something (or trying to avoid it) — of desire.

But let’s face it, objects are treasure. There is that truly strange phenomenon of fetishism and its relative, money. That is not, however, what I want to consider…

It is extremely difficult for an object to lie. Often someone makes an object dishonestly, and presents it as something that it is not. People are deceived for a while, then upon discovery of the deception discard the object. At that moment grace descends, (or perhaps ‘ascends’ is more appropriate). The object itself never lied. As we now see it in the vacant lot or garbage dump, its brave, confessional honesty shines. ‘Yes, I am plastic and glue and impermanent paint’, it proclaims with humble courage. As an act of saintly generosity it further explains, ‘Don’t worry, I’m completely useless.”[9] — Jimmie Durham

“To search for the law governing signs is to discover the things that are alike. The grammar of beings is the exegesis of these things. And what the language they speak has to tell us is quite simply what the syntax is that binds them together. The nature of things, their coexistence, the way in which they are linked together and communicate is nothing other than their resemblance.”[10] — Michel Foucault

“A needle driven into a tabletop.

A pen nib driven into a lemon rind.

A nail file driven into a box.

A safety pin driven into a piece of cardboard.

A nail driven into the wall, right above the floor.”[11] — Witold Gombrowicz

“If everything about matter is real, if it has no virtuality, this means that the object’s medium is spatial. The object, while it exists in duration, while it is subject to change, does not reveal more of itself in time: it is ‘no more than what it presents to us at any given moment.’(Bergson) By contrast, what duration, memory, consciousness bring to the world is the possibility of an unfolding – a narrative – a hesitation. Not everything is presented all at once.”[12] — Elizabeth Grosz

“The thing must be understood not only as an object of human thought, as in the idealist view, which distinguishes between thought and matter, but as actually constituted by human praxis, as in the materialist or monist view, which resists that distinction as ideologically motivated.”[13] — Christina Kier

“DYNAMICS OF THE IDEAL. The subject exists only inasmuch as it identifies with an ideal other who is the speaking other, the other insofar as he speaks. A ghost, a symbolic formation beyond the mirror, this Other who is indeed the size of a Master, is a magnet for identification because he is neither an object of need nor one of desire.”[14] — Julia Kristeva

“To understand a real object in its totality we always tend to work from its parts. The resistance it offers us is overcome by dividing it. Reduction in scale reverses this situation. Being smaller, the object as a whole seems less formidable. By being quantitatively diminished, it seems to us qualitatively simplified. More exactly, this quantitative transposition extends and diversifies our power over a homologue of the thing, and by means of it the latter can be grasped, assessed and apprehended at a glance.”[15] — Claude Lévi-Strauss

“La diferencia, pues, entre las dos maneras de contemplación que venimos explicando, puede expresarse simbólicamente diciendo, que para la critica histórica, el sujeto se incorpora al mundo histórico a que pertenece el objeto, mientras que para la simple crítica, el objeto es incorporado a la cultura de quien lo hace motivo de su contcmplación.” (The difference, then, between the two manners of contemplation that we arrive at explaining, can be symbolically expressed by saying that for the critical history the subject incorporates the historical world that pertains to the object, while for the simple criticism the object is incorporated to the culture that motivated the contemplation)[16] — Eduardo O’Gorman

“Despite the use of this terminology [fetish] in a variety of disciplines that claim no common theoretical ground – ethnography and the history of religion, Marxism and positivist sociology, psychoanalysis and the clinical psychiatry of sensual deviance, modernist aesthetics and Continental philosophy – there is a common configuration of themes among the various discourses about fetishism. Four themes consistently inform the idea of the fetish: (1) the un-transcended materiality of the fetish: “matter”, or the material object, is viewed as the locus of religious activity or psychic investment; (2) the radical historicality of the fetish’s origin: arising in a singular event fixing together otherwise heterogeneous elements, the identity and power of the fetish consists in its enduring capacity to repeat this singular process of fixation, along with the resultant effect; (3) the dependence of the fetish for its meaning and value on a particular order of social relations, which it in turn re-enforces; and (4) the active relation of the fetish object to the living body of an individual: a kind of external controlling organ directed by powers outside the affected person’s will, the fetish represents a subversion of the ideal of the autonomously determined self.”[17] — William Pietz

[1] Theodor W. Adorno, Rolf Tiedemann, and Shierry Weber Nicholsen, “The Handle, the Pot, and Early Experience,” in Notes to Literature, vol. 2 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1991), 219.

[2] Djuna Barnes and T. S. Eliot, Nightwood (New York: New Directions, 2006), 9.

[3] Georges Bataille and Georges Bataille, “Sacrifices and Wars of the Aztecs,” in The Accursed Share (New York: Zone Books, 1991), 58.

[4] Walter Benjamin, Howard Eiland, and Michael William. Jennings, “Spain, 1932,” in Walter Benjamin: Selected Writings., vol. 2 (Cambridge, MA: Belknap, 2005), 643.

[5] B. H. D. Buchloh, “Marcel Broodthaers: Open Letters, Industrial Poems,” in Neo-avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975 (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000), 91-92.

[6] Bill Brown, “Thing Theory,” in Things (Chicago: University Of Chicago Press, 2004), 3.

[7] Aimé Césaire, Clayton Eshleman, and Annette Smith, “Solar Throat Slashed: At the Locks of the Void,” in Aimé Césaire, the Collected Poetry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1983), 203.

[8] Ewa Domanska, “Forum on Presence: The Material Presence of the Past,” History and Theory 45 (October 2006): 339.

[9] Jimmie Durham, “The Wonder of Humanity in No Particular Order,” Things That Fall, section goes here, accessed September 01, 2013, http://www.thingsthatfall.com/jimmie-durham.php.

[10] Michel Foucault, “The Prose of the World,” in The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences (New York: Pantheon Books, 1971), 29.

[11] Witold Gombrowicz, Cosmos, trans. Danuta Borchardt (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2005), 79.

[12] E. A. Grosz, “Philosophy, Knowledge, and the Future,” in Time Travels: Feminism, Nature, Power (Durham: Duke University Press, 2005), 106.

[13] Christina Kiaer, Imagine No Possessions: The Socialist Objects of Russian Constructivism (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005), 69.

[14] Julia Kristeva, “Freud and Love: Treatment and Its Discontents,” in Tales of Love (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), 35.

[15] Claude Lévi-Strauss, “The Science of the Concrete,” in The Savage Mind ([Chicago]: University of Chicago Press, 1966), 23.

[16] Eduardo O’gorman, El Arte O De La Monstruosidad (Mexico City: Conaculta, 2002), 78.

[17] William Pietz, “The Problem of the Fetish II,” RES: Anthropology and Aesthetics, no. 13 (Spring 1987): 23, accessed October 23, 2012, http://www.jstor.org/stable/20166762.