02 01

Vol. 02 Issue No. 1

Read the Journal: site95_Journal_02_01.e

Editor in Chief MEAGHAN KENT, Contributing Editor JANET KIM, Copy Editor BETH MAYCUMBER, Copy Editor JENNIFER SOOSAAR

Guest Curator LAUREN VAN HAAFTEN-SCHICK

Journal designed by SITE, Logo designed by Fulano, All images credit: Lauren van Haaften-Schick

Marfa, TX

Texas is enormous. The land is mostly desert with its endless sky. The road stretches for miles, causing the optical illusion of infinity, akin to staring at the ocean. Even in winter, mirages appear on the sand and asphalt. Everything here is marked by a contradiction of unpredictability and control.

Donald Judd’s Chinati Foundation, housed in the remains of the military base Fort D.A. Russell, is comprised of permanent installations by eleven artists, including Dan Flavin, Sol Lewitt, and Roni Horn, which fill the base’s former meeting-houses, infirmaries, and sleeping quarters. School No. 6 by Ilya Kabakov is a fabricated Soviet elementary school classroom where the holes in the exterior walls are left unfilled, allowing sand to blow in, coating an already aged patina. John Wesley’s surreal figurations, dependent on their own odd sense of repetition, stand out as the sole moment of whimsy. Everything was selected and overseen by Judd. A massive installation of his signature aluminum boxes, each with facets in unique configurations, fills two hangars that once housed German prisoners of war. A hand-painted sign that translates: “Use your head or lose your head” looms above the works.

The Chinati Foundation is located in downtown Marfa and exhibits a behemoth permanent installation of works by John Chamberlain. It is home to the Judd Foundation offices, the late artist’s architecture and design workshops, studios, and house. A new generation of art businesses, visitors and investors have developed nearby. On Highland Street, going south from City Hall, one passes an art book store, at least five galleries, an Andy Warhol permanent work, as well as artists’ and crafters’ studios. Around the corner, on San Antonio Street, there is a line of newly refurbished Airstream trailers serving coffee and tacos. Across the street is Marfa Montessori. The town is an amusement. Everything is stylized to maintain the myth of authenticity. At the perimeter are crashed trailers, crumbling houses, broken fences, and then nothing but the desert.

Just further are Judd’s home and studio, swathed in a nine-foot high adobe wall. It is the original addition to the town, built in the time after Camp Marfa, when the town was seemingly abandoned. This barricade served to block all that could have distracted Judd from his work in the studio and library, ensuring privacy and refuge from a world deemed too loud, quick, opportunistic and prying. A preservation team is currently working to keep it that way.

Visitors en route to Marfa, TX must first pass through El Paso. Formerly overshadowed by Juárez, its sister city just south of the border, El Paso has in recent years absorbed the clubs and restaurants that once gave Juárez its fabled night-life. The highway and a paved river divide the two cities. Looking down at Juárez from the end of Scenic Drive, the view is surreal and other worldly. This is as much of the now infamously violent city that we dare see.

Eventually, everything changes.

There is a brief mountainous pass on Highway 10 just east of El Paso, right before Van Horn. This is the last sign of civilization before one turns south to go towards Marfa, Big Bend National Park, and ghost town after ghost town.

Oil rigs dot the highway in West Texas, standing as kinetic monuments in an otherwise barren landscape. They each have their own tempo, and continue undisturbed by the harsh winds and sand storms that blow through. The air smells like gasoline.

The horizon is lined in purple mountains. Nothing looks as though it has any depth or dimension. It’s possible that not all of it is real.

About an hour east of El Paso, in Van Horn and Sierra Blanca, there are road signs warning against picking up hitchhikers.

For Judd and the artists he invited to Marfa, the potential for permanent siting of a work in this open land gave it new purpose.

In the early sculptures I used anything made of steel that had color on it. There were metal benches, metal signs, sand pails, lunch boxes, stuff like that. . . . Body shops would cut parts away and I would choose what I wanted from whatever was in their scrap pile. . . . I wasn’t interested in the car parts per se. I was interested in either the color or the shape or the amount. I didn’t want engine parts, I didn’t want wheels, upholstery, glass, oil, tires, rubber, lining . . . none of that. Just the sheet metal. It already had a coat of paint on it, and some of it was formed… I believe that common materials are the best materials.

—John Chamberlain

It takes a great deal of time and thought to install work carefully. This should not always be thrown away. Most art is fragile and some should be placed and never moved again.

—Donald Judd

Somewhere a portion of contemporary art has to exist as an example of what the art and its context were meant to be. Somewhere, just as the platinum-iridium meter guarantees the tape measure, a strict measure must exist for the art of this time and place.

—Donald Judd

Spanish curves, adobe and the horizontal utility of ranch-style buildings merge in the architecture of the southwest Texas desert. Structurally preserved yet cracked or faded by the sun, it is impossible to tell how old some things are. There is often nothing for miles on either side.

The art and architecture of the past that we know is that which remains. The best is that which remains where it was painted, placed or built. Most of the art of the past that could be moved was taken by conquerors. Almost all recent art is conquered as soon as it’s made, since it’s first shown for sale and once sold is exhibited as foreign in the alien museums. The public has no idea of art other than that it is something portable that can be bought. There is no constructive effort; there is no cooperative effort. This situation is primitive in relation to a few earlier and better times.

—Statement for the Chinati Foundation/La Fundacion Chinati, Donald Judd, excerpt.

Art and architecture — all the arts — do not have to exist in isolation, as they do now. This fault is very much a key to the present society. Architecture is nearly gone, but it, art, all of the arts, in fact all parts of the society, have to be rejoined, and joined more than they have ever been. This would be democratic in a good sense, unlike the present increasing fragmentation into separate but equal categories, equal within the arts, but inferior to the powerful bureaucracies.

—Statement for the Chinati Foundation/La Fundacion Chinati, Donald Judd, excerpt

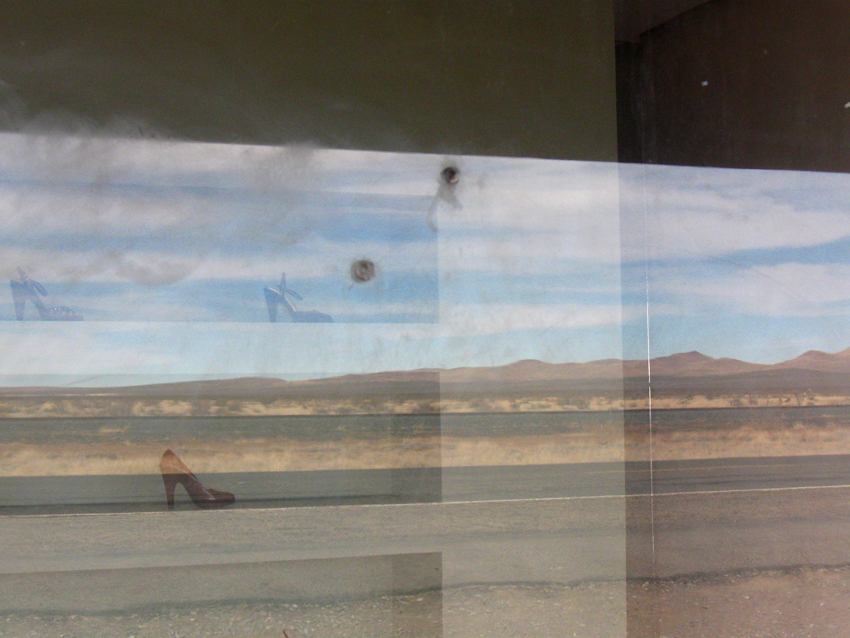

On the edge of Valentine, Texas, on California Avenue just northeast of Marfa, Prada Marfa nearly blends in with the other shuttered shops along US 90. Though it houses the Prada fall 2005 collection of handbags and shoes, the doors are sealed shut and the shop has never been open for business. Sometimes, a pickup truck with tinted windows parks across the road, waiting for visitors to come and watching as they leave.

Michael Elmgreen & Ingar Dragset, Prada Marfa, 2005. Commissioned by the Art Production Fund and Ballroom Marfa.

The Stardust Hotel had crumbled before the slow start of Marfa’s transformation in 1972, when Judd moved to the former military town from New York. He wrote of passing through nearby Van Horn while enrolled in the Army in 1946–1948. Journal entries are filled with observations of the empty landscape and vast open sky. The military base that now houses his Chinati Foundation was defunct by the end of World War II, and its buildings were left to decay.

A relic of the late Deco-era boom of life in Marfa, the Stardust sign is one of the few remaining traces of the region’s past incarnation. Once Judd moved into the downtown he erected a wall around his home, built from the bricks of an abandoned hotel. Maybe it was the Stardust.

We first went to Marfa together in 1996. Judd was dead. The town was dead. Chinati was in mourning. Tumbleweeds the size of shopping carts blew down the wide streets — with no one even there to photograph them. There were a handful of Tex–Mex cafés with flyswatters on the tables and a drive-through window at the local bar. Nearly every storefront on Highland Avenue leading up to the courthouse was empty, save the ones installed with artwork by Judd.

—Sean Wilsey and Daphne Beal

The old theaters downtown are relics of Marfa’s earlier status as a military hub and resort for local ranchers.

The Paisano Hotel, just next door to the Texas and Palace theaters, is now included in the National Register of Historic Places. Buffalo heads and painted tile adorn the walls, creating a kind of Spanish lodge, a look and feel familiar to past generations as a more authentic Americana.

The concierge of the Paisano, a late middle-aged Mexican-American woman, has lived in Marfa her entire life and began working at the hotel as a teenager. Having moved her way up from a position with the cleaning staff, she now checks in guests and takes reservations for dinner. First in line is a group of three college-aged blonde women wearing cocktail dresses and all carrying the same black handbag and mini rolling suitcase. After checking in, they ask three times whether the concierge is serious when she says there is no elevator to take them to the second floor. Next, a pair of young men ask where the bar is and if there is a happy hour. They are wearing vintage shirts, have casually long hair and beards and one of them has thick black-framed circular glasses. The concierge tries to find this unremarkable.

Third in line is another couple, a white woman and a Mexican man. They give the man’s name, Alonso, for their dinner reservation.

“Oh, your name is Alonso,” the concierge says. “Maybe you’re my brother.”

“Hm, I don’t think you’re my sister…”

“I always wondered… My father died before I was born, and I always thought, maybe I have brothers and sisters I don’t know about, so maybe you’re my brother. I grew up here with my mother, we always lived in Marfa, sometimes in Alpine a half an hour away, but mostly here where I also have two aunts. You look like the pictures of my father.”

“How did your father die?”

“He was in a car accident, a crash right outside Van Horn, on the highway between here and El Paso. There is a mountain ridge at Allamoore, on the 10. They just found him there, maybe he fell asleep, don’t know what happened.

—conversation from the Paisano Hotel

Ry Rocklen, Second to None, 2011

The land in parts of southwest Texas is divided as an ordered grid, defining ranch and farmland properties. It is completely linear.

A personal fortress downtown, Judd’s home and studio are repurposed military storage facilities. One wonders how the rigidity, flatness, and dependence on the grid within his work was informed by the desert and plains of southern Texas.

Judd’s transitional piece from painting to sculpture, housed here, is a floor work comprised of a bright orange curved sheet of plywood held to an arc by three planks affixed to the ends. There is a section of black pipe running through and connecting both, like a portal.

Complementing the aesthetic and ethic of the late artist’s work, every experience of its exhibition is highly mediated. There is no photography allowed.

Judd’s comprehensive design and architecture studios in a former supermarket downtown are also completely concealed.

Dan Flavin, Untitled (Marfa Project), 1996

Completed after Judd’s death and when Flavin himself was ailing, a reviewer from The New York Times deemed the work, “The Last Great Art of the 20th Century.”

Donald Judd, 15 Untitled Works in Concrete, 1980

This series of two and a half by two and half by five meter concrete structures were the first additions to the Chinati complex. When the piece was introduced, ranchers joked that the hollow boxes were square drainage culverts, and a neighbor is said to have overly watered a tree outside their bedroom window until it blocked their view of the boxes altogether.

Judd’s pristinely kept, closely guarded home and its neighboring installations in Marfa represent the ultimate experiment in environmental control.

Upon entering the expansive permanent installation of Judd’s aluminum boxes at the Chinati Foundation, visitors are lectured on the staining effect of body oil on aluminum, and are watched at all times by one or more docents. Conservators do a sweep of the building after every tour. The buildings, which formerly housed two hundred German POWs during World War II, have been retrofitted with floor to ceiling exterior glass walls.

The space is a vitrine in the wild desert, utopian and oddly innocent.

Fences, doors, gates, and barriers are all engineered with the same precision as the sculptor’s infamous boxes. The proportions are always symmetrical. They are designed to last, and to keep out any intruding element.

A visitor to Marfa from Dallas mused on the influx of tourists and the burgeoning art economy over the past few years. Businesses seem to be doing well, and yet, like the native locals, this population keeps to its own.

To Donald Judd,

… As we leave the Chinati Foundation, my grandfather’s house is on the left at the traffic circle. Completing the circle are the public housing complex and the US Border Patrol office. The Border Patrol tower shines its light down on the area. Behind Hipolito’s former home there is an altar housing a statue of the Virgin de Guadalupe. The main structure of the altar is a discarded bathtub turned on its end and partially buried in largest tree in the yard. I tell you how the altar is there to mark an apparition of Guadalupe in 1994, coincidentally, the year of your passing. The apparition appeared at night for two weeks as a white shadow in the tree trunk. There is film footage of this phenomenon on a single decaying VHS tape. She appeared to Hector Sanchez, whose family lives in the house now. He passed shortly after completing the altar in 1997. He is survived by his wife, Ester, who has no difficulty maintaining both her belief in the auspiciousness of the apparition as well as her hypothesis that it was “caused” by the light from the Border Patrol tower coming through the tree’s leaves…

Perhaps you have never noticed the altar before. It has also drawn pilgrims for years, from Mexico, New Mexico and the local area, but these pilgrims are different from those who visit your works, and likely they have never taken notice of one another either.

We continue walking north and east. A few blocks and we are at the Blackwell School. Now a mostly inactive landmark, the school was historically where students of color in the area gained their education. Small and isolated as it is, Marfa experienced the same racial segregation in public education as did the rest of the country in the last century. Now it is a quasi-museum, and in large letters across the east facing exterior wall we see a quote in black florid script: “Caminante, no hay puentes, se hace puentes al andar.” Beneath that a name: Gloria E. Anzaldúa…

“In her book Borderlands/La Frontera, there is a subsection titled ‘Invoking Art.’ In it she distinguishes the dominant “Western aesthetic” by its operations of setting up rigorous systematicities, then demonstrating a virtuosic mastery of those systems. I understand this as aptly describing most work canonized in the discipline of art history, from geometrically driven Renaissance painting to your own impulse toward seriality, constructed ratio-systems and pristine materiality…

Against this, Anzaldúa poses the work of her “people, the shamans” for whom art is inseparable from everyday life. This work is immediately spiritual and political, in that spirituality is a source for political (read communal) action for them and for her. Here, an example we both now know might be the altar to Guadalupe’s apparition in Marfa. The motivations behind its construction are wholly different from your own. They come from a Mexican American Catholicism that carries traces of pre-Colombian figuration manifest in colonially imposed forms and mythologies. It was constructed to mark a site not by meticulously manipulating light and physical space but by alluding to the supernatural, the sacred that is invisible most of the time but markedly auspicious when present…

The binary Anzaldúa constructed is not satisfactory for me, and I understand border thinking as a method by which to address my dissatisfaction. Speaking solely from the example of your work, the first half of the binary allows no space for understanding the political, philosophical work moving through the manipulation of metal, concrete and plexiglass. It makes no space for investigating the large body of writing and activism you left behind. You have thought importantly and much about the conditions of the country where we live, and been critical even of its critics. As your own writing and the work of scholars like David Raskin have demonstrated, you rigorously investigated anarchism, the politics of space and the problems of centralized government, and investigation is inextricable from the ratios and systems that guided your pen and hand in designing the works and spaces you have left us in Marfa and elsewhere. The latter part of the binary leaves no room for investigating the form of an object like the altar. Giving primacy to its allusiveness to the supernatural beyond disallows, or makes difficult, a reading of the object as congealed labor. How are we to discuss the Mexican factory from which the statue was sourced and its complicity with racist capitalism? Or the local Marfa hands who painted it as imbricated in the discourse of scarcity, labor and resources in West Texas?

I wonder what you might have thought of all of this…

—Josh T Franco, Letter to Donald Judd, September 2012

Thirty minutes east of the town is the viewing station for the Marfa Lights. The first recorded sighting of the phenomenon was in 1883 when a rancher camping near Paisano Pass spotted a series of mysterious flashes in the night sky. They were known among the Native Americans long before. In 1947 a local pilot attempted to fly to the lights at night and get close to them, but once he was in the sky they were nowhere to be found. After this first failed mission, the pilot tried again twenty years later with the aid of observers in cars and planes. Neither trip yielded any information.

The lights often appear in pairs aligned at ten-to-twenty degree angles. Some say they are ghosts of the Spanish Conquistadors, or spirits of the Native Americans’ ancestors. Sometimes they disappear as soon as they are noticed. There are accounts of people being pursued by them. Roswell is only about a five-hour drive away.

Their cause remains a mystery.

We drove up to the Marfa lights viewing station and everything looked abandoned. Then we saw a girl standing in the road, her head covered by a white piece of cloth, and slowly waving her arms. We pulled over and rolled down the window to ask her if it was closed, to which she replied in a sing-song voice “It’s always open…”

There was a rustling sound the whole time we were there.

When we left the viewing platform there was a white car parked right out front that we never heard pull up.

It’s not the lights from the cars. It’s not a traffic light.

One time I heard someone singing.

When we got back in our car I went to put my hand in this little box that we had kept open, storing souvenirs we’d collected along the way. But somehow, while we were out watching the lights, the box had been closed.

Owner: NBC News

Date: 7/5/85

Title: APPEARANCE OF MODERN ART SURPRISES MARFA RESIDENTS

Location: Marfa;Texas

Era: 1980s

Personalities: Judd, Donald

CAR DRIVES DOWN HIGHWAY. HIGH SHOT OF MARFA SEEN. TRAIN MOVES DOWN TRACKS. TOWNEE SITS OUTSIDE. ABSTRACT ART IN THE FORM OF CONCRETE BLOCKS IN FIELD SEEN. AERIALS OF CONCRETE BLOCKS SEEN. MAN LOOKS AT BLOCKS. IN INTERVIEW MAN SAYS HE THOUGHT THE CONCRETE PIECES WERE MEANT FOR A NEW HIGHWAY. ANOTHER MAN CONTENDS THE BLOCKS WOULD MAKE NICE BACHELOR QUARTERS. MAN ASSERTS HE DOESNT KNOW MUCH ABOUT ART AND NOTES THE BLOCKS MAKE NICE HOMES FOR ANTELOPE. ANTELOPE ROAM NEAR CONCRETE BLOCKS. ART CREATOR DONALD JUDD (PH) SKETCHES. IN INTERVIEW JUDD SAYS HE IS USED TO PEOPLE LAUGHING AT HIS ARTWORK. JUDD WALKS THROUGH TOWN. EXTERIORS OF MARFA MUSEUM SEEN. DISPLAY OF CRASHED AUTOMOBILES AND ALUMINUM SCULPTURES SEEN IN SIDE MUSEUM. JUDD CONTENDS HE IS TRYING TO MAKE REALITY WITH HIS SCULPTURES. SUN SETS OVER CONCRETE BLOCKS.